Enhancing Case Definitions with Genomics

How genomic data can be used to build better case definitions

One of the core concepts of applied epidemiology is defining outbreaks, who is in and who is out. It’s not always as easy as it sounds! Some outbreaks are classic point-source outbreaks where everyone has a discrete event or exposure in common - the wedding reception, choir concert, etc. In those cases it’s usually pretty straightforward to build a case definition based on the clinical presentation and limits on time and place. In other cases it’s much more difficult, for example in an acute care hospital which receives many transfer patients in their ICU. If they see a concurrent increase in Klebsiella pneumonia cases in both their ICU and general floor can they easily define whether that might represent one outbreak, two outbreaks, or not an outbreak at all?

What is a case definition

Let’s back up and first define our definition. Probably a good practice. So what exactly is a case definition? It’s a set of uniform criteria that can be applied to determine whether a person is counted as having a health condition or being included in a cluster or outbreak. Today we’ll focus on outbreak case definitions, which are a little more narrow and customized than standardized surveillance case definition which are used for routine disease monitoring.

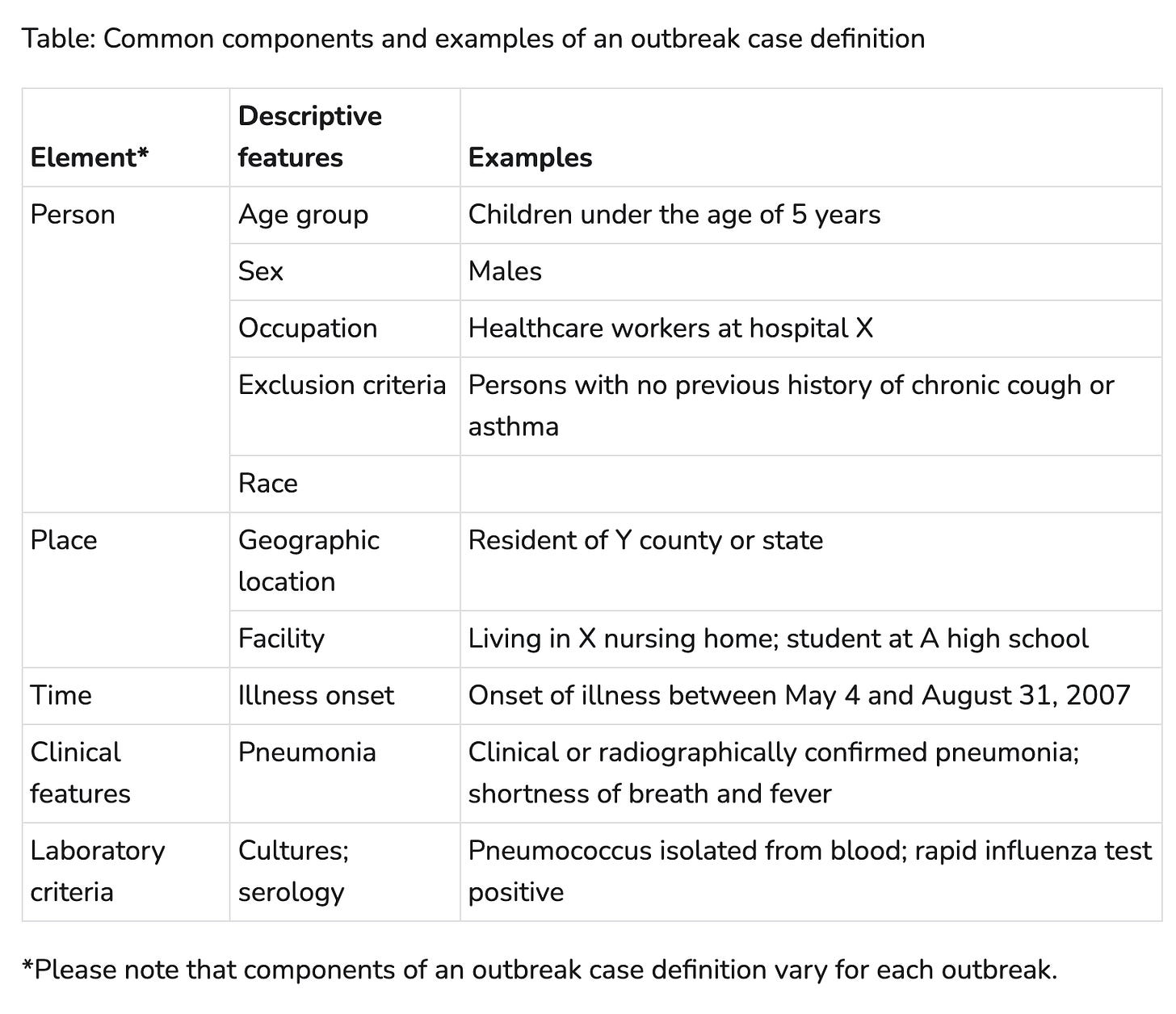

Case definitions are typically made up of a few parts - person, place, time, clinical, and laboratory criteria. Not every outbreak will have every aspect included, but this is pretty good start. The table below from the CDC’s Outbreak and Case Definition site gives some examples of how those elements can be applied.

That seems pretty comprehensive, right? But let’s revisit our hospital example. Are there elements in the case definition that would help distinguish between two concurrent outbreaks? You could have a place-based restriction and define that patients with only exposure to the ICU are part of one outbreak, and patients with no ICU exposure as part of another outbreak. But how would you know if that definition accurately classifies the cases?

Misclassification: The Enemy of Analysis

So, why is it so important to be able to accurately classify people as in or out? Why does it matter if we call it one outbreak or two concurrent outbreaks in a facility? One big reason is that misclassification makes it really difficult to look for statistical associations between exposures and illness, which makes pinpointing the source of the outbreak extremely difficult.

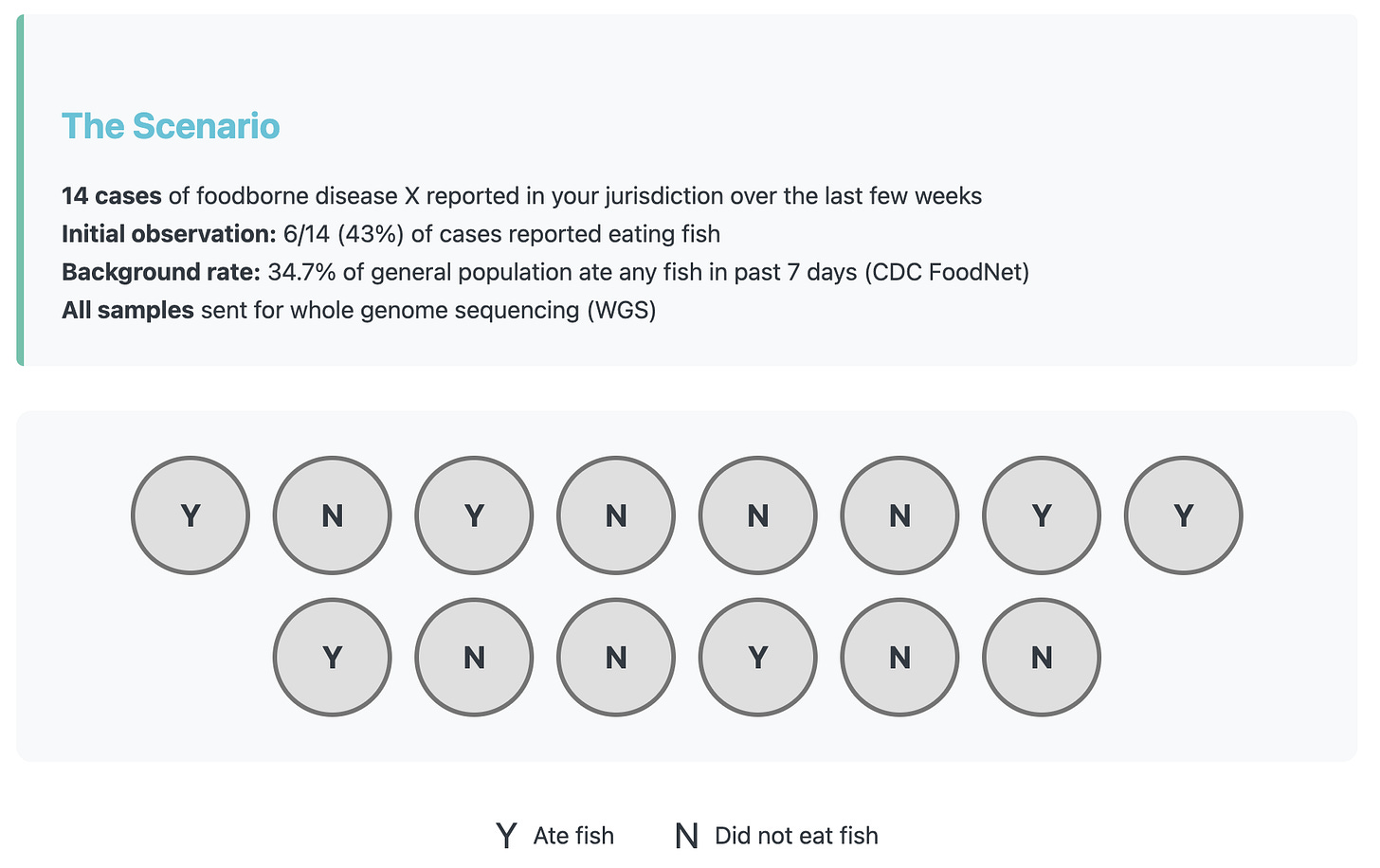

Lets make up an example to show how misclassification can completely change the outcome of an analysis. In our scenario there are 14 cases of foodborne disease X in your jurisdiction over the past two weeks. While you wait for the sequencing data to come in, you take a first look and notice that 6/14 (43%) of the cases reported eating fish during their exposure period. That piques your interest, but when you compare it to the reported background rate which is 34.7% it’s not too different.

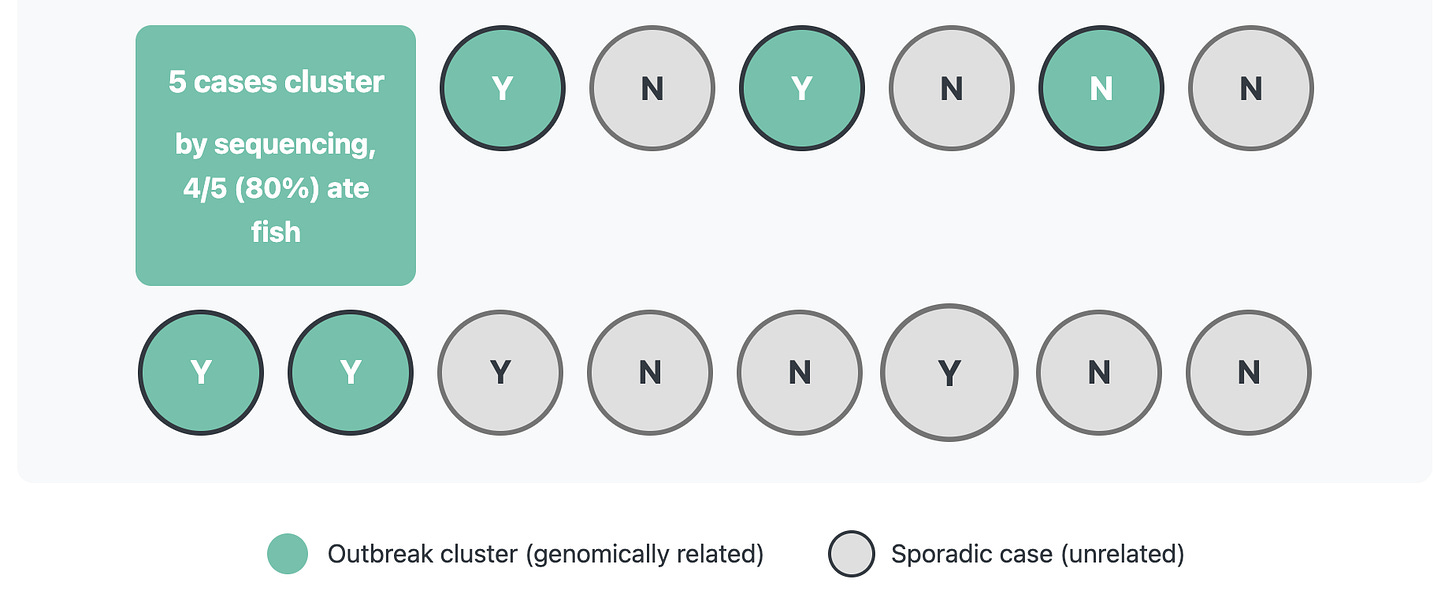

After sequencing, you find out that only 5 cases are closely related by sequencing, and of those 5 cases 4/5 or 80% ate fish. That’s a much stronger signal! By narrowing our case definition through incorporating sequencing data, it is much easier to sort out the signal from the noise in the exposure data and narrow down what exposures should be investigated further.

How to incorporate genomic data in case definitions

So, now that you’re convinced how helpful it can be, how can you actually implement this in practice? The outbreaktools.ca website has some great examples to peruse, and I’ll share a few more here.

The first one comes from an outbreak of P. aeruginosa in eye drops, as documented in this publication.

Cases were defined as a US patient’s first isolation of P. aeruginosa sequence type 1203 with carbapenemase gene blaVIM-80 and cephalosporinase gene blaGES-9 from any specimen source collected and reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during 1 January 2022–15 May 2023

The next one comes from an outbreak of E. coli O121 in Canada as documented in this publication.

A confirmed case was defined as a person infected with E. coli O121 between August 1, 2018, and November 30, 2018, visiting or residing in BC, with an isolate matching within 10 alleles by whole genome multi-locus sequence typing (wgMLST).

The last one I want to highlight comes from a Hepatitis A outbreak in Canada as documented in this publication.

A confirmed case was defined as a resident of or visitor to Canada with laboratory-confirmed HAV infection with genotype 1A and one of two genetically related outbreak RNA fingerprints; an onset date on or after 1 October 2017; and no close contact with a confirmed case 15 to 50 days prior to illness onset.

These have the traditional elements, but specifically incorporate information derived from sequencing, such as sequence type, specific antimicrobial resistance genes, and genotype. This allows for much more narrowly defining your cluster for investigation.

Internal and external references

There are two types of information shared in those case definitions - in some you’ll notice references to how the cases within the outbreak are related to each other - things like “within 10 alleles” and “genetically related outbreak RNA fingerprints.” I’ll call these internal references. While these are certainly useful ways for teams to define cases during their investigation, it makes it challenging to communicate to anyone outside of that investigative team either during or after the outbreak.

The other pieces of information you’ll notice are ones that reference things like “genotype 1A” and “sequence type 1203.” These are values that are meaningful for people outside the immediate investigating agency, which makes it possible for others to answer the question of “have I seen any sequences matching this cluster/outbreak in my agency or facility. I call these external references, because they use points of references outside of just your cluster cases, and this allows for others to be able to make comparisons.

How to make your definitions more valuable

If an outbreak is occurring, it should be easy for any agency or facility that is conducting sequencing to be able to identify if they have cases that meet the case definition. That is much easier said than done though! Often relatedness is determined using internal-only pipelines and databases, and definitions like ‘within 10 wgMLST alleles” may be perfectly sufficient for the investigating agency. So what can you do to make it easier for others to be able to connect the dots?

Be as specific as possible in your genomic piece of the case definition, including defining or unique features like a specific combination of AMR genes or virulence factors.

Use widely available methods and terminology, MLST is not the most specific, but it does have standard schemes available.

Share at least one example sequencing in a public sequencing repository to allow for genomic comparisons

Going back to the example from the eyedrops Pseudomonas outbreak, it’s such a unique combination of genes that you can even build a query using the NCBI pathogen detection tool to find sequences that match the outbreak case definition - how cool is that! Even more helpful, if you create an account and log in to NCBI you can save your search and get email alerts every time new sequences get added that meet your query criteria. Way easier than logging in regularly to check.

Wrapping it up

I hope you’ve been inspired to think carefully about how you can use information derived from sequencing to make more accurate case definitions, and how this can help focus your investigations and increase the odds of successfully identifying the source. Incorporating genomics in your case definition also makes it much easier to connect across different organizations, between animal and human health, and all across the globe.

Happy sequencing!

References:

P. aeruginosa in eye drops outbreak: Ellington MJ, Ekelund O, Muhsin F, et al. Multistate Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST1203 Coproducing VIM Carbapenemase and GES Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Through Contaminated Eyedrops, United States, 2022–2023. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30(5):1027-1031.

E. coli O121 outbreak in Canada: Hexemer A, Reimer A, Peterson CL, et al. Escherichia coli O121 Outbreak Associated with Flour—Canada, 2018. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2020;17(11):670-678.

Hepatitis A outbreak in Canada: Hayward K, Pabbaraju K, Berenger BM, et al. Frozen Berries as a Source of a Large Multi-Jurisdictional Outbreak of Hepatitis A, Canada, 2012–2019. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2021;18(9):638-644.

Additional Resources Mentioned:

CDC Outbreak and Case Definitions. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/urdo/php/surveillance/outbreak-case-definitions.html

Outbreak Tools Canada. Available at: https://outbreaktools.ca