I am excited to introduce you to Dr. Miguel Paredes, who I had the pleasure of collaborating with on a project as part of his recently completed PhD studies. We recently sat down at the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists conference to talk about his educational path to date, his future plans, and his perspective on the future of the field of genomic epidemiology. I hope his story is helpful to everyone, but it is especially relevant to those early in their academic career who are considering possible courses of study that lead to genomic epidemiology.

Academic pathway:

B.S. Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, Yale University

M.P.H Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases, Yale University

Ph.D. Epidemiology, University of Washington

Current program: M.D., University of Washington

Miguel didn’t start his academic journey with an interest in genomic epidemiology, and initially had a keen interest in developmental neuroscience. While he was doing research in this area, he was also drawing on his own experience as an immigrant from Colombia by providing translation and advocacy services for immigrants from Latin American countries. This volunteer experience gave him a sense of urgency for work that would serve communities now, not just research that would provide benefits in the distant future. He began to realize that research in neuroscience was very long-term and future-focused, and that it may not be the direction he ultimately wanted to pursue.

The Zika virus outbreak gave Miguel the opportunity to combine many of his interests: infectious disease, science of the brain, helping communities in Latin America, and contributing to impactful public health work. He had the opportunity to work on Zika as he was earning his MPH degree, and the experience contributed to his selection of the next phase of his educational journey – the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) at the University of Washington, which is a dual degree program where students earn both a medical degree and a PhD, taking an average of 8 years.

In the MSTP, students are free to choose their PhD discipline, and as he considered his options, epidemiology was the clear choice. As Miguel told me, “epidemiology is the basic science for human populations,” and studying epi allowed him to “use the quantitative side of his brain in a way that is broader than basic biology.”

So, where does genomic epidemiology finally come into the equation? The Department of Epidemiology at the University of Washington School of Public Health has very strong interdisciplinary relationships and allows their students to work with advisors from a wide range of backgrounds. Miguel elected to do his PhD research with Dr. Trevor Bedford, a Professor at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center who focuses on viral phylodynamics. Through his PhD studies, Miguel combined the knowledge and methods he learned within the Bedford lab with his biological background from his undergraduate degree and epidemiology studies from his MPH and PhD coursework. It is hard to think of an academic pathway more suited for genomic epidemiology than that combination!

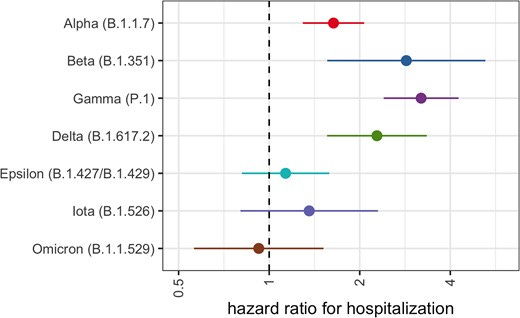

It was at this stage of Miguel’s academic journey that our paths crossed. I was working at the Washington State Department of Health focused on data integration – collecting sequencing data from more than a dozen labs that were routinely sequencing SARS-CoV-2, and along with a team of other epidemiologists, connecting this sequencing data to the clinical and epidemiologic data in our state disease surveillance database. What we in governmental public health at the time didn’t have though, was the bandwidth to conduct formal studies on this rich dataset we were so focused on compiling. It was a perfect opportunity for a talented and driven PhD student, and Miguel took on the work with endless enthusiasm and efficiency. He worked closely with our team and other partners to conduct an analysis of SARS-CoV-2 variant severity, which was published in Clinical Infectious Diseases and formed part of his PhD dissertation. This was one of the first US-based studies that was able to systematically address variant severity - see the figure below for the wide range of variants that were included in the study.

Why genomic epidemiology?

I asked Miguel why he chose to approach this work from the epidemiology angle, rather than focusing on computational biology, virology, and other more laboratory-based sciences. There are a multitude of reasons, but fundamentally, he wants to make sure that the “epidemiology” piece in genomic epidemiology doesn’t get lost. Epidemiologists work with messy real-world data that can’t be generated under controlled conditions in a lab, and good epi work requires deep thinking about sampling methods, study design, biases, confounders, and analysis methods. “I got to introduce DAGs to the lab” Miguel said with a chuckle, as evidence of his work bring tools of traditional epidemiology into the phylogenomics lab (see figure below for more on DAGs). Genomic epidemiology isn’t simply slapping additional data fields onto a phylogenetic tree. Epidemiology is also deeply tied to communities, and that perspective allows the computational and biological research to be connected to real-world action and better address the “so what” questions when it comes to how pathogen genomics can be used in public health.

Example of a directed acyclic graph (DAG)

Go check out the full paper above to learn more about what DAGs mean and why they are important tools in epidemiology.

Future plans and reflections

While most people would be resting on their laurels after completing their PhD (he successfully defended his dissertation on May 22, 2024), Miguel will be back to school in the Fall for his final two years of medical school, adding clinical skills to his already impressive breadth of training. Wherever Miguel ends up contributing in the future after that final graduation ceremony, he will bring his perspective as a talented and well-trained genomic epidemiologist.

We discussed his thoughts on the different academic journeys someone could take if they were interested in genomic epidemiology. Though his pathway was focused on the biology and epidemiology aspects, he emphasized the need for multiple disciplines and perspectives. There is a need for people to work in the genomic epidemiology sphere that have backgrounds in mathematics, social sciences, communications, visual design (“color changes the world!”), and many other disciplines. I appreciated his reminder of the breadth of skills needed, and that you don’t have to follow the same path he did to be able to find a place in the exciting field of genomic epidemiology.

I hope that his story is an inspiration for students as well as the existing public health workforce. If you’d like to keep up with Miguel, you can follow him on Twitter (I know, I still call it that) or LinkedIn.

I appreciate Miguel taking time to share her story with me! Do you incorporate genomic data into your work as an epidemiologist? If you’d like to share your career journey, reach out to krisandra@genomicepi.com.