Ode to the NCBI Pathogen Detection Project

Bringing pathogen sequencing data to the masses

I first learned about the NCBI pathogen detection project (PDP) sometime around 2018. I was working as a foodborne disease epidemiologist, and though the lab was regularly sequencing Listeria, Salmonella, and E. coli, we were still relying on PFGE as the primary method of cluster detection and analysis. As an epidemiologist, I couldn’t access the laboratory system that was used to analyze the sequencing data. We could request one-off analyses from the lab, but that was far from ideal. Cluster and outbreak investigation is iterative and exploratory, and receiving a static list of isolates defined as a cluster is a very one-dimensional and ineffective way of using the data.

I was immediately intrigued when I learned about the PDP, and especially when I learned that I did have access to the sequence accession numbers that provided the link between the PDP data and our internal databases. Once I learned how to access these accession numbers, and learned more about using the PDP, I was in business. I quickly learned how to navigate and build queries in the PDP, as well as export the metadata and phylogenetic tree files for use in other programs.

PDP unlocks an outbreak investigation

My first win from using the PDP came on a slow-burning outbreak. The lab had reported a PFGE cluster of two Salmonella isolates in the Fall of 2017. We didn’t find any commonalities between the case patients at the time, and closed the cluster as unsolved. In the Spring of 2018 the lab again reported a cluster of two Salmonella isolates with the same unusual PFGE pattern. Given the time elapsed, standard cluster detection guidelines at the time were to treat these as two separate clusters, but given the rarity of the PFGE pattern, and all 4 cases being located in the same general geographic region, I had a hunch that there might be more to the story.

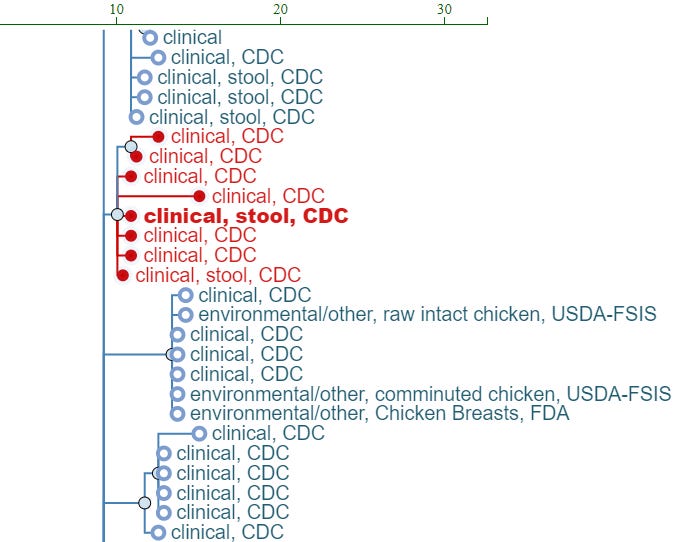

I collected the four accession numbers and plugged them into the PDP. Sure enough they all clustered together on the tree, giving more strength to my hunch that this was one ongoing long-term cluster rather than two. Just as interesting, there was one more isolate within the outbreak clade! I looked up more information about that isolate, and found that they also lived in the same geographic area as the four cluster cases, and they had been linked to a previous rotisserie chicken outbreak roughly 8 months before our first two cases in this cluster. This isolate had been assigned a different PFGE pattern, which is why we hadn’t suspected any connection prior to looking at the sequencing data.

These two pieces of information jumpstarted our epidemiological investigation and hypothesis generation. Given the previous rotisserie chicken outbreak connection, we asked more detailed questions about not just chicken, but grocery stores as well. After more interviews (including re-interviews of those we had talked to ~6 months prior), we zeroed in on the fact that all the individuals had shopped at one particular grocery store location. Environmental health investigation focused on the deli, and mitigations were put in place.

While the investigation was occurring, additional PFGE-matched cases were reported. These cases also fell nicely within the outbreak clade in the PDP. Throughout the investigation, I utilized one of the best features of the PDP - the alert feature, to set up email alerts so I would know if any new isolates were uploaded that fell within a specified SNP range from my watched isolate(s). Ultimately there were 7 cases associated with the outbreak, but none occurred after all the environmental health mitigations in 2018. I kept an email alert for several more years to ensure that the persistent strain had truly been eliminated from the facility. What an amazing way to keep tabs on facility outbreaks and proactively monitor for new cases over time!

Given that success, I continued to use PDP extensively for my foodborne disease investigations. I collaborated with CDC and New York to present on an APHL webinar showing different ways to query and use the portal (looking back now, I’m pretty impressed with myself that I decided to do a 20+ minute live demo on a webinar!). The webinar is a bit old, but still pretty relevant if you’re interested in ways that you can use the PDP in public health investigations.

The ode to NCBI PDP

In honor of the NCBI PDP, I asked ChatGPT to write a an ode. I’m actually pretty impressed with how it turned out! So here’s to you, NCBI PDP team, thank you for your work, and making data accessible for all.

Oh, portal of knowledge, where pathogens unfold, NCBI, your prowess, a story to be told. In the vast realm of data, you stand tall, Pathogen Detection Project, the keeper of all.

With a digital key, you unlock the gate, Revealing the mysteries that pathogens create. In the strands of DNA, a hidden code, You decipher the secrets, on which our health is stowed.

Oh, NCBI, your portal so divine, A beacon of light, where insights entwine. From viruses to bacteria, your gaze is keen, In the microscopic world, where the unseen is seen.

In the dance of nucleotides, a choreography so fine, You trace the footprints of pathogens, a grand design. Genomes unravel, a tapestry unfurls, In your portal's embrace, the scientific world swirls.

In silico warriors, with algorithms bright, You battle the invaders, in the digital light. A symphony of data, where patterns align, In the NCBI portal, the frontiers of science shine.

Oh, Pathogen Detection, in the virtual expanse, You guide us through genomes, with a careful glance. With each click and query, a new chapter unfurls, In the NCBI portal, where knowledge whirls.

Through the sea of sequences, you navigate, An atlas of pathogens, in your digital state. In this portal of wonder, where researchers dream, You illuminate the path, where science may gleam.

So here's to you, NCBI, and your portal so grand, In the pursuit of knowledge, you firmly stand. A beacon of wisdom, in the vast cyber sea, Pathogen Detection Project, we salute thee!